BY CHRIS BARNETT / Journal of Commerce

Article published Wednesday, January 30, 2019, in www.joc.com

Under the influence of a “super cycle” driven by tax credits, approximately 38,000 megawatts of wind farm development were under construction or in advanced development in the US by the third quarter of 2018, up 28 percent from the same period in 2017. Overall, total installed wind capacity had reached 90,550 megawatts in November, according to the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA). When those projects are completed, installed capacity will have increased another 42 percent. And, thanks to the increasing viability of wind-based energy production and the vagaries of tax law, the building boom should continue through at least 2023.

For wind-related project cargo logistics, that equates to a lot of business, as well as a high risk of congestion and equipment shortages.

Anthony Long, general manager for global supply chain sourcing at GE Renewable Energy, says the wind power industry is going through a “super cycle” similar to 2012, when the Internal Revenue Service introduced the Production Tax Credit (PTC) to promote development of renewable energy. “There is a rush to cash in, and [it’s] an opportune time for developers; but we also think the long-term market for wind energy and wind turbines is strong,” he said.

GE is a trailblazer that has grown with the industry, said Long, citing the company’s recently created two-piece blade for its Cypress onshore turbines, an innovation in design and logistics. On the latter, the blades drive down logistics costs by enabling assembly on site, reducing the need for permitting equipment and roadwork, according to a GE brief. “The high-tech carbon blades create a new flexibility of transport,” Long said.

John Lusty, director of energy and utility solutions for Siemens Gamesa Canada, said the adoption of renewable energy has been “far greater than we anticipated and that’s not slowing down, especially in light of recent reports from the United Nations and research organizations that confirm climate change is real and the effects of carbon dioxide-free emissions is exponentially beneficial. We’re moving massive pieces of equipment in a heightened level of activity to execute installations of [qualified] wind farms before that PTC window closes.” Although the incentive doesn’t end until 2023, projects must be producing energy by then to receive the tax credit.

Arturus Espaillat, senior manager of transportation for manufacturer Vestas, agrees. “The phase-down of the PTC is certainly driving a surge in installations as project developers and owners work to meet the PTC qualification deadlines in a very active overall economy,” he said in an email interview with The Journal of Commerce. He cites a forecast from energy consultant Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables that installations will top out at 11 gigawatts annually in 2019 and 12 gigawatts in 2020, then scale down “to more sustainable levels.”

Larger turbines

This logistics activity level is not new, Espaillat said. The industry experienced high-volume installations in 2012. “The difference this time around is on turbine size. Blades have gone from 150 feet in average length to over 200 feet,” he said. Greater lengths and weights add new “execution challenges” such as police escorts and night travel that “stretch the available capacity of the transportation industry.”

But, he added, heavy-haul transport companies that left wind a few years ago to serve other booming industries are coming back.

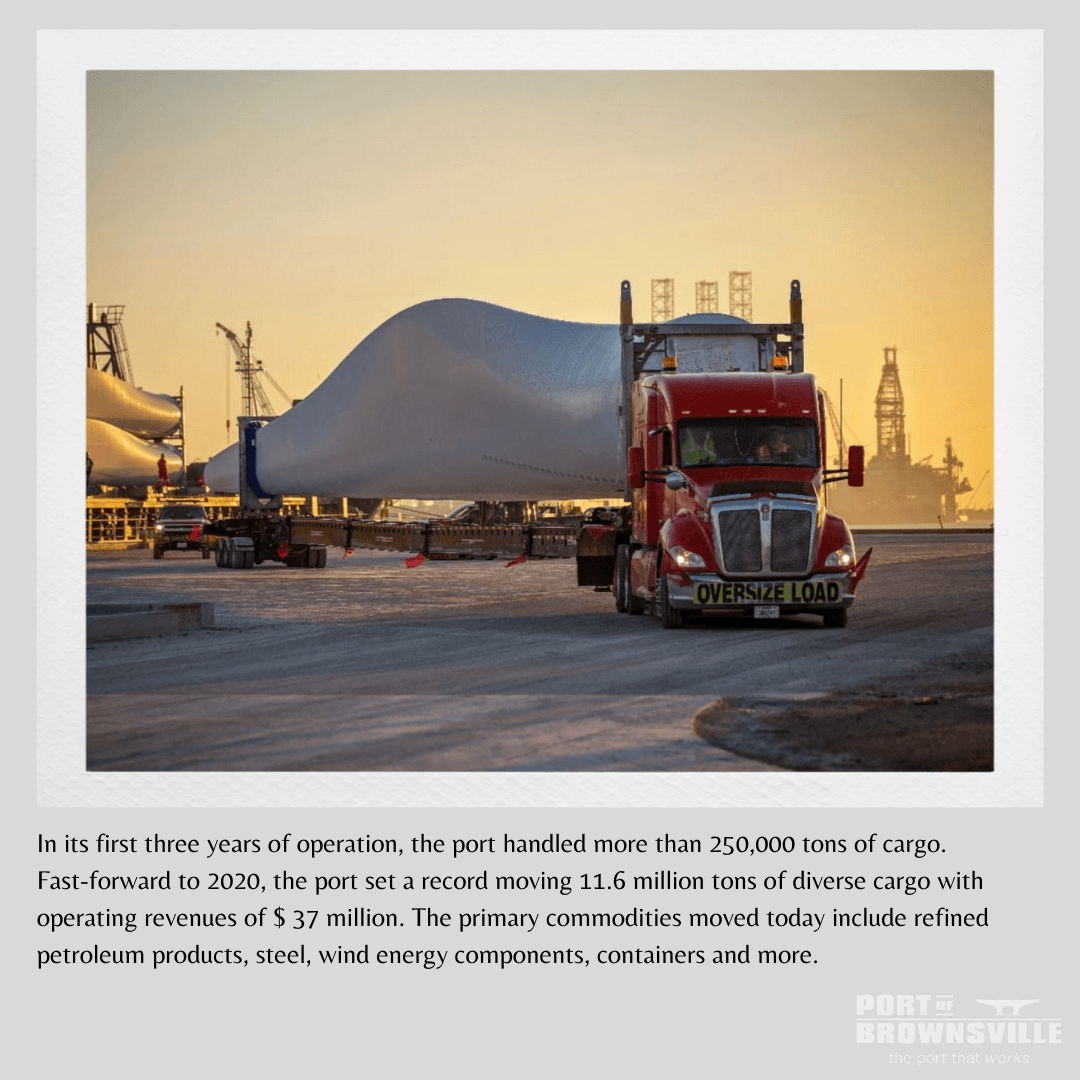

Moving a disassembled 300-foot-tall wind turbine overland is a quintessential project cargo challenge — and a single turbine makes only a dent in the ever-growing demand for energy production. But to attain critical mass and electrify a geographical grid, it takes a farm of wind turbines, not a solo shipment. For the first time, land-based towers capable of generating 4 megawatts and powering 1,400 homes a year were installed in the third quarter of 2018, according to the AWEA.

St. Cloud, Minnesota-based Anderson Trucking Services (ATS) has developed a prowess for moving these project cargoes. “We saw the birth of the wind industry in the early 2000s, made the strategic investments in equipment like the Schnable multi-axle trailer where we can grab each end of the turbine’s tower section and, through the magic of physics, keep it ‘floating’ while it’s being transported,” explained Gene Lemke, ATS’s vice president of projects.

ATS has transported more than 200,000 wind components since 2003. “Right now, with the [PTC] expiring, [turbine] manufacturers are racing to get their bids out to market so they can beat their competitors in locking up transportation capacity,” Lemke said. “We already have projects booked through the fall of 2019, and we are now having to walk away from some business due to lack of capacity.”

ATS has a fleet of 110 wind blade trailers (when loaded with a 228-foot blade, one trailer is as long as 14 mid-sized sedans), 90 Schnabel trailers for hauling turbine tower sections, and other trailers capable of transporting wind components such as nacelles and hubs.

As blades lengthen, ATS is investing in the next generation of blade trailers and collaborating with a trailer manufacturer to design a customized blade trailer. ATS, however, monitors the wind market closely, and “we’re staying somewhat conservative,” Lemke said. His company expects the market to slow after 2021 and then pick up around 2025, “when the new higher-output turbines help to render the expired federal tax credit irrelevant and the economics of projects become more favorable.”

Demand surge boosts prices

Meanwhile, the surge in demand is pushing up pricing, Lemke said, stopping short of discussing specific rates or percentages. “It is the simple demand-supply equation, and right now there is a lot of competition for assets,” he said.

Lone Star Transportation, a Fort Worth, Texas-based heavy hauler running 400 trucks including owner-operators, also specializes in moving wind tower components and has “several major projects” booked through 2019. Demand for capacity is strong, equipment manager Joe Byrd said.

Keeping pace with the ever-expanding physical dimensions of an onshore wind turbine, which can be as tall as 300 feet — almost the full height of the Statue of Liberty — when installed, is a continuing challenge for heavy haulers. In 2001, a nacelle (the power generating unit of the turbine), was rated at 0.6 megawatts, weighed 40,000 pounds, and moved on a normal, over-the-road double-drop trailer, Byrd said. Today, a 2.5- to 3-megawatt nacelle can weigh 168,000 pounds and moves on a four-unit, 13-axle rig that could extend more than 100 feet on the road and requires escorts, he said.

BNSF Railway is advising wind farm developers to move components well in advance of installation deadlines. “We also encourage our customers to have a laydown yard that can be used for staging components on the ground for last-mile truck deliveries,” said Theresa Lorinser, the railroad’s marketing director for industrial products.

She said the industry has invested in new multipurpose railcars, so the surge in development and transportation isn’t impacting the availability of equipment. “As blade lengths grow, it does not necessarily change the way railcars function,” she said. “The concentration will still be centered around how the blade moves on a railcar. We have shipped blades that have extended over three 89-foot railcars.”

G2 Ocean, a joint venture formed by Gearbulk and Grieg Star in 2017, operates a fleet of open-hatch vessels and conventional bulkers, transporting forestry products, steel, and project cargoes including wind. Long blades fit nicely on G2 Ocean vessel decks, according to one shipper.

G2, which handles wind blades, towers, and nacelles from Asia through the Texas ports of Brownsville, Corpus Christi, Galveston, and Houston, expects “a very big year in wind components,” chartering director Andy Powell said.

Several US ports, many in the Gulf, are expecting a surge in wind cargo during the next 24 months. Corpus Christi serves as the gateway to a “wind corridor” that runs from Texas through New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, and as far north as Nebraska, said Maggie Iglesias-Turner, the port’s business development manager for wind energy and project cargo. Although trucks primarily serve these regions, a decent proportion of blades leave the port by rail.

“Manufacturers in the next two to three years will be very, very busy,” Iglesias-Turner said. The phasing out of the PTC will push developers “to get their components to the jobsite as quickly as possible to take advantage of the PTC as we know it.”

Despite tariffs, she expects China, South Korea, Brazil, and Europe to be key sources of wind imports into the US. Wind components take up a lot of space, itself a valuable commodity that many US Gulf ports are able to offer developers. Corpus Christi has added 25 acres of laydown space, bringing the port’s total to 100 acres.

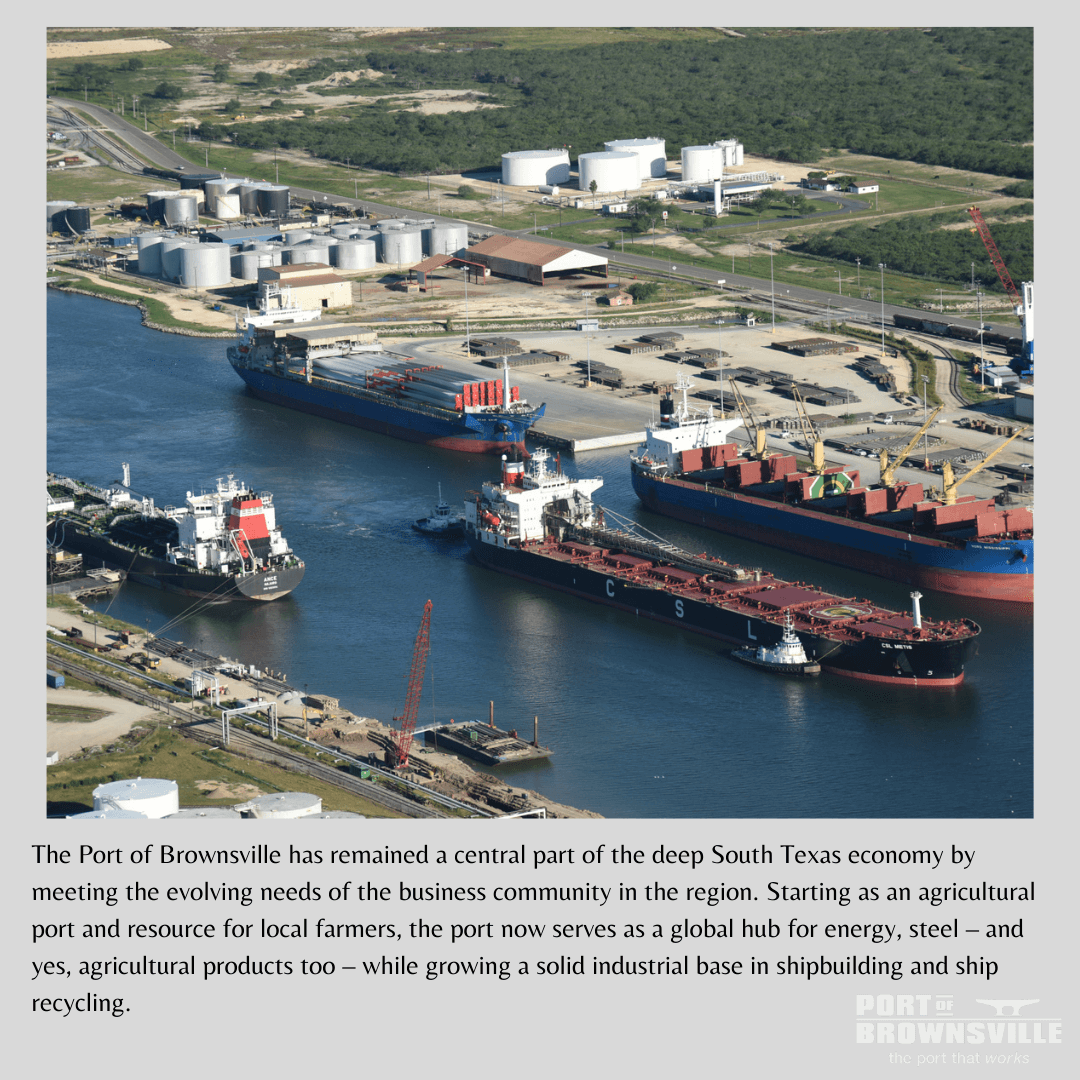

Wind components are also important at Brownsville, on the Texas-Mexico border and where imports are bound for US and Mexican wind farms, said Steve Tyndall, senior director of marketing and business development. The port generally handles three major wind energy projects a year, he said. “So far, we have two lined up for next year, and I’m confident we will have a third before this year is out,” he said in late 2018. “2019 should be a good year for us.”

Brownsville also hopes to become a wind blade exporter, thanks to TPI Composites, a global blade manufacturer based in Scottsdale, Arizona. TPI is building two blade manufacturing plants in Matamoros, Mexico, near Brownsville, that will begin operating this year, and produce 3,000 blades a year, according to Tyndall. “I don’t know if we’re going to get a large slug of that cargo, but we can certainly handle it,” he said.

Gulf ports don’t have a lock on wind power logistics. The Port of Duluth, Minnesota, handled its first wind turbine component shipment in 2005. More than 90 percent of the wind components imported into the port move out by truck — west to Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado; north to Alberta, Canada; and south to Missouri and Oklahoma.

“Our Duluth Cargo Connect team has seen [wind] freight tonnage go up and down with the [enactment of] the [PTC] but we’ve made port improvements to accommodate the increasing size and weight of these units,” said Adele Yorde, public relations director for the Duluth Seaway Port Authority. “We have the experience in handling wind components. We have 40 acres of outdoor storage and laydown. We spent $20 million on reinforcing our dock for heavy-lift cargo and adding more crane capacity,” she said. “We are ready.”