BY STEVE CLARK/ The Brownsville Herald

Article published May 3, 2017

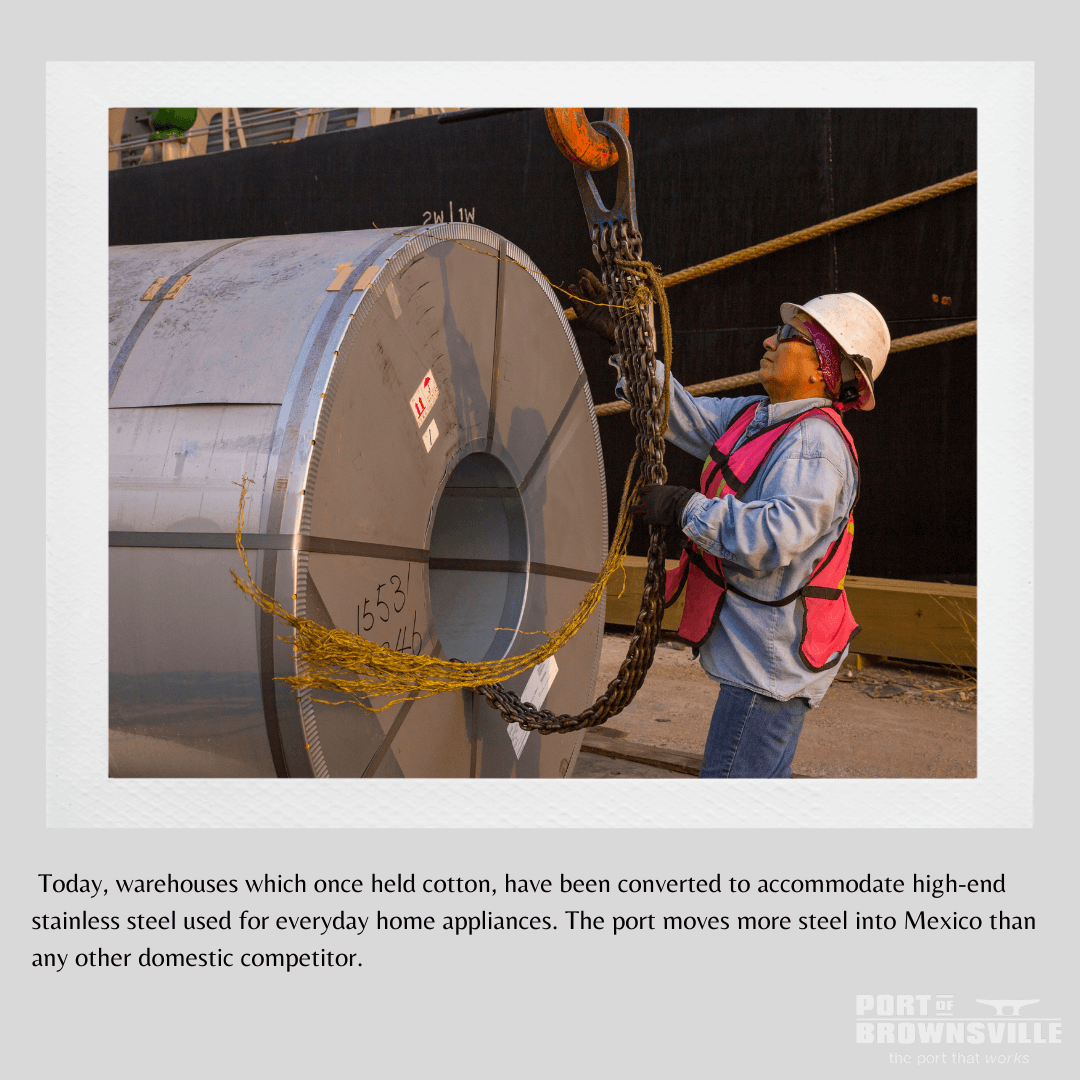

BROWNSVILLE – The Port of Brownsville is closer than it’s ever been to finally landing a steel mill, something it’s been pursuing for decades. Brownsville is one of two finalists for a $1.5 billion, advanced flex steel mill identical to Big River Steel’s new plant in Osceola, Ark., the world’s first LEED-certified facility of its kind.

LEED stands for “Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design.” According to the U.S. Green Building Council, LEED is the world’s most widely used green-building rating system. Big River is expected to decide within a few months whether to build a new mill in Brownsville or expand its Arkansas operation.

The new project has been dubbed “Project America.” Port officials say it would directly support 500 new full-time jobs with a minimum annual salary of $75,000. The mill primarily would supply the automotive and vehicle component industries in Texas and Mexico.

Alan Simon, vice president of industrial development for Denver-based OmniTRAX, which is in charge of developing the port’s industrial base, said Arkansas attracted the first Big River Steel facility through major cash incentives via the state legislature.

“Texas is a little bit different, but one of the programs that we hope will be very instrumental in this is Chapter 313,” he said. “We’ve been having discussions along those lines in hopes that that program could come into play and be a factor in attracting them with some property tax abatement.”

Tax Code Chapter 313, or the Texas Economic Development Act, allows a school district to offer a temporary limit on school property tax on the value of new investment. In this case, Point Isabel ISD would be able to defer by eight years when the steel mill project goes on the tax rolls at full value. The limit on the taxable value doesn’t kick in until the third year of the project.

Simon said the project would require two years of engineering and permitting, and two years of construction. He said Big River wants incentives worth at least 10 percent of the project’s $1.5 billion cost, or $150 million. That percentage is typical for similar projects around the country, Simon said.

“We hope we get to that point,” he said. “We’re certainly going to do the best we can, and then the company will make their decision. We’ve been working just on the incentives piece of it for several months, and we’ve probably got another month of work to pull that all together.”

Besides the abatement, key incentives would come in the form of land discounts and bond financing from the port and OmniTRAX; capital investment from OmniTRAX parent company The Broe Group; and Texas Enterprise Fund and Texas Enterprise Zone assistance through the Brownsville Economic Development Council and Greater Brownsville Incentives Corporation.

Eduardo Campirano, port director and CEO, said port officials have tried for decades to attract a steel mill, though an insufficient supply of electricity in the Brownsville area always was the main stumbling block. Recent upgrades to the Rio Grande Valley’s power grid have eliminated that obstacle, he said.

Campirano said Brownsville is a strong contender for the project since the port produces more scrap steel than anywhere else in the country, and Big River uses scrap steel for its feedstock. That obviously benefits Brownsville’s recyclers, though the port still wouldn’t be able to meet all the mill’s feedstock needs, he said.

Big River would produce 1.6 million tons of steel a year and require feedstock of about 2 million tons a year, Campirano said. Brownsville’s recyclers, operating at top capacity, would supply no more than 500,000 tons a year, he said.

That’s also good for the port, however, since it would boost barge activity through scrap steel imports, Campirano said. That’s why one of the two potential sites for the mill is on the ship channel. The other site is on port property off S.H. 550 north of S.H. 48.

“That means all our recyclers are going to be busy, the tugboat captains, everything that goes into that sector of it,” he said.

The mill would also support the numerous service and supply-chain companies that would inevitably follow a steel mill, Campirano said.

“It’s a substantial project, a lot of great-paying jobs,” he said.

Simon said Big River takes “mini-mill” technology a step further by using scrap steel. In addition to the jobs and ancillary benefits, it’s a desirable project because of the LEED designation and nothing like the heavily polluting steel mills of decades past, he said.

“They’ve taken a lot of steps to achieve that certification so that they’re friendly to the environment,” Simon said. “What they’ve told us, it benefits them in the supply chain because the customers give them some preference, because they’re paying attention to those things. If they were not using recycled steel and not paying attention to all this, it would certainly be a much greater impact.”