Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following question-and-answer (Q&A) column as part of a regular interview series with experts in the Mexican natural gas market.

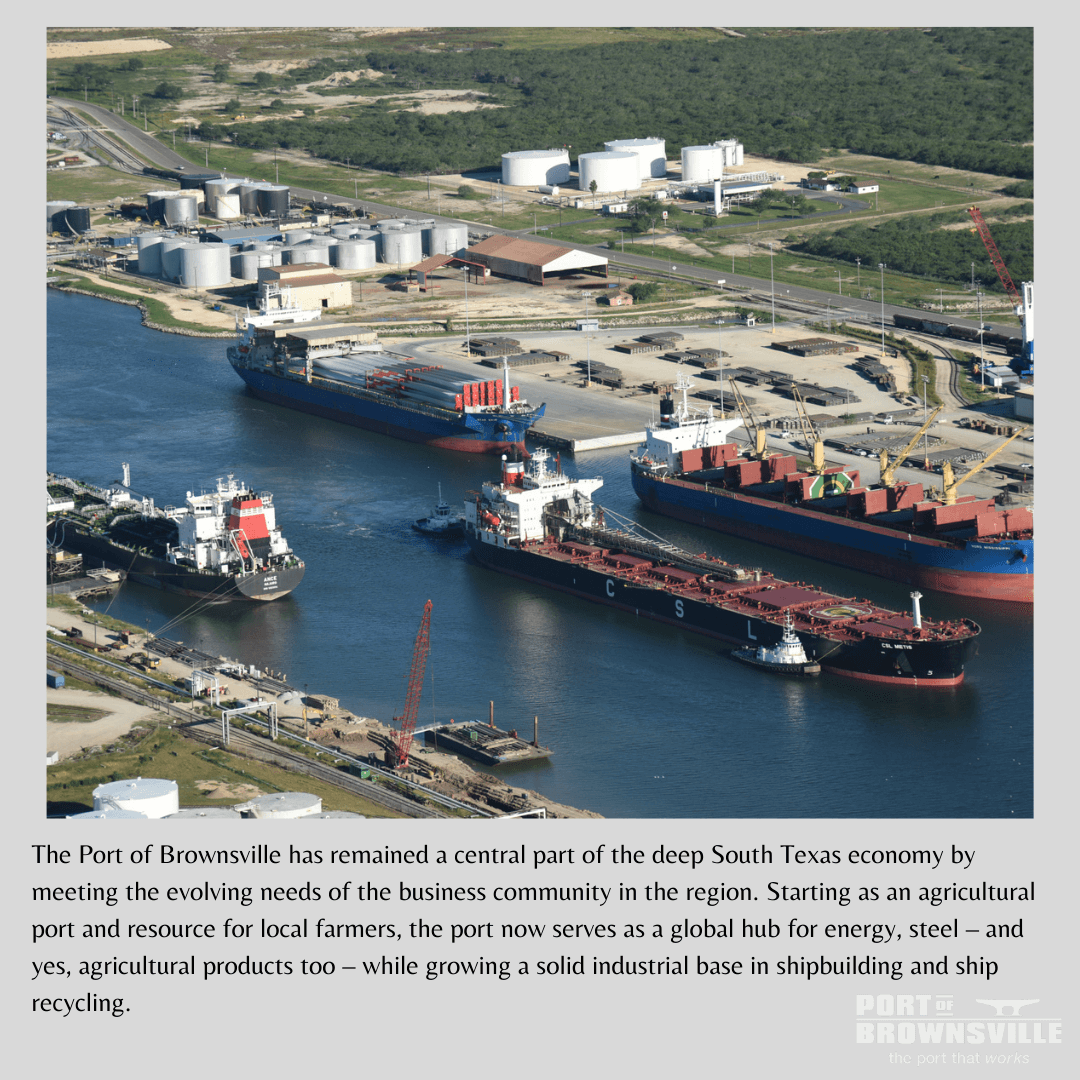

This 22nd Q&A in the series is with Eduardo A. Campirano, Port Director and CEO of the Port of Brownsville, the only deepwater port on the U.S.-Mexico border. Since his appointment in 2007, the Port of Brownsville has improved its financial position by increasing its cash reserves, issued debt for infrastructure improvements, undertaken major road and infrastructure improvements and repairs, and has attracted port-related investments through public and private sector partnerships.

Campirano’s public service extends to his active participation in numerous civic and maritime industry organizations and committees.

Adam Williams / NGI

NGI: What is the role of the Port of Brownsville and, given its border location, how does it facilitate the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico?

Campirano: The simple way to start the conversation is to say that we are essentially an in-transit port where we import a lot of commodities from domestic or international markets and turn around and export them to another international market. In our case, it’s really all Mexico. A lot of our focus and a significant percentage of what we do is focused on trade with Mexico.

Some of the primary commodities included in that trade are in the refined product market. We ship a lot of premium gasoline, ULS diesel, jet fuel and lubricants to Mexico. A lot of our business is predicated on the ability to serve that logistics platform so that when the commodities arrive, they are transshipped to their final destinations in Mexico. That is a big part of what we do.

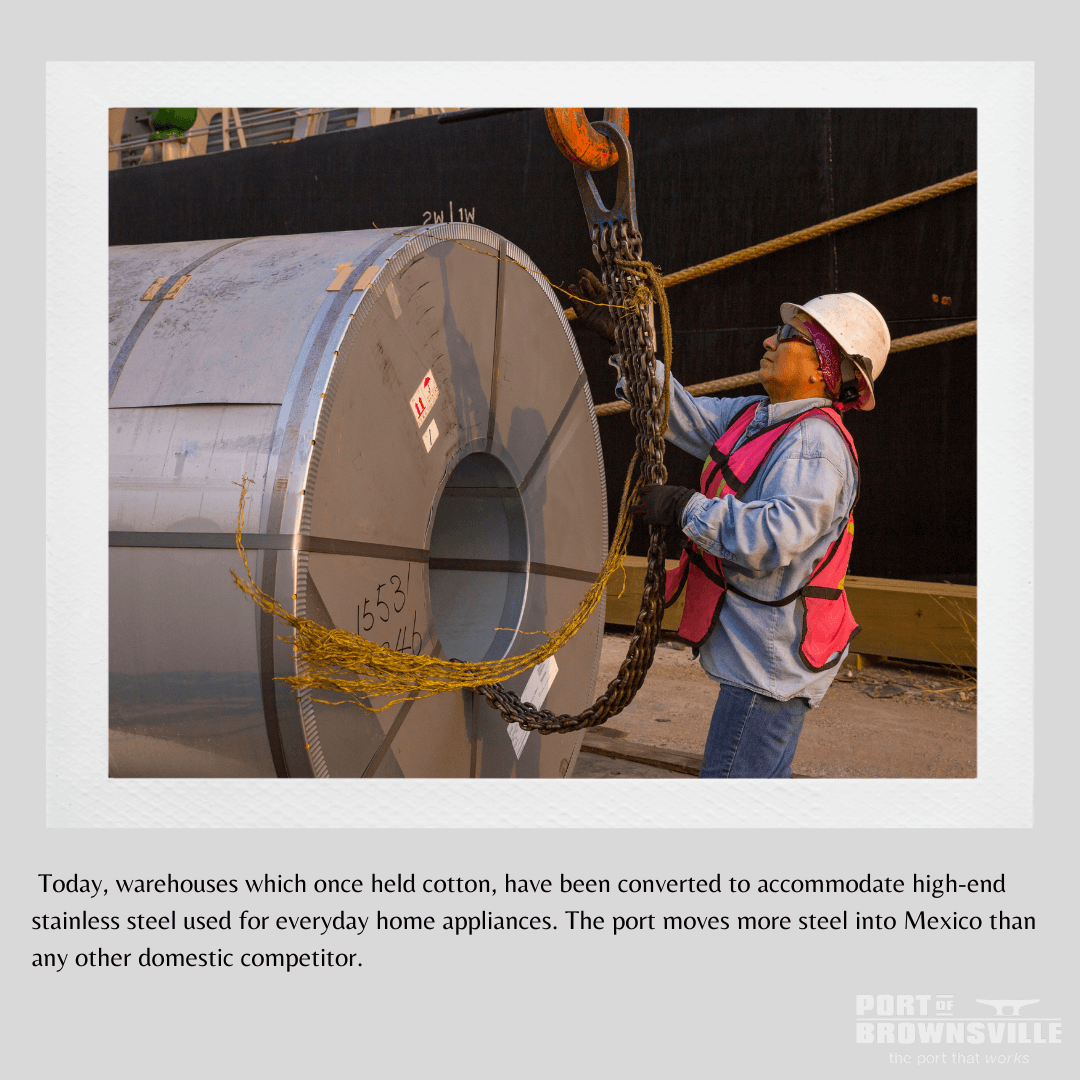

We also do a lot of steel, especially in terms of the steel that serves as the feedstock to the mills in Monterrey. Ternium is a huge customer of ours. We move more than 3 million metric tons of steel in and out of the port, with Ternium alone accounting for more than 2 million tons. We serve as that logistics platform to import that commodity by vessel and then ship it to Mexico, with a majority of that being moved by rail.

Mexico trade is a very significant and integral part of the port’s business. But then again, we’re on the border with Mexico and we continue to be heavily, heavily involved with the cross-border trade that exists between Mexico and the state of Texas and Mexico, and the U.S.

NGI: Has the Port of Brownsville seen an increase in energy-related product shipments into Mexico following the country’s energy reform in 2014?

Campirano: I would say yes. The energy reform changed how a user of energy-related commodities, primarily liquids such as gasoline and diesel, can acquire those products. Previously, they had to go through Pemex. Now they can go out and acquire the commodities through their own resources. The demand for the refined product market has been increasing year-in and year-out since the energy reform.

The energy reform created more opportunities for all the different market players. I think it’s all been good. It continues to drive demand and having a location where you can import large volumes and export large volumes — either to the interior of Mexico or the border, or whatever the case may be – which certainly has been a plus for us, and the market is continuing to grow.

One example is the Valley Crossing Pipeline natural gas project developed by Enbridge that was built to deliver Eagle Ford shale natural gas to Mexico, primarily to the Altamira and Tuxpan areas. That project goes right through the Port of Brownsville. As I understand it, that pipeline project now provides Mexico with a significant amount of its natural gas needs. That has opened up opportunities for us on this side of the border that could in the future provide more opportunities in Mexico.

You are also starting to see discussions about product pipelines being built into Mexico. Hopefully some of that might originate here. We do, for example, have pipeline connectivity to Matamoros and some of the terminals there that move gas and diesel into the interior of Mexico. We also have pipeline connectivity to Burgos, as well as to Cadereyta.

As a border port and the only deep-water seaport on the U.S.-Mexico border, and having been involved with cross-border relations, we have been in the business of supporting Mexico’s growth for a long time. And it’s been mutual.

NGI: Are there any other natural gas pipelines that connect at the Port of Brownsville or are expected to connect at the port in the future?

Campirano: There are three proposed LNG projects here at the port. In November, all three received their FERC permits. Those projects are in the works.

Included in that is the Río Grande LNG project, which also includes the Río Bravo Pipeline project. In the FERC filing on the NextDecade project (owner of Rio Grande LNG and Rio Bravo Pipeline), they are planning to provide their own gas to their own facility. It is the largest of the three LNG projects at the port. The Rio Bravo Pipeline project is actually two pipelines that will connect to the Agua Dulce hub and bring gas to the Río Grande LNG project. It follows a similar route as the Valley Crossing project.

The two other LNG projects are Annova LNG and Texas LNG. We pretty much know that on the Annova LNG project, Enbridge is a 10% stakeholder, meaning they will deliver the natural gas for the Annova project. The other project, Texas LNG, has publicly stated that they are going to be looking at a third-party provider for natural gas. You’re going to see natural gas coming here for those facilities, and as far as additional natural gas pipeline infrastructure, that will be driven by the Río Grande LNG project.

NGI: The first year of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration has just completed. Did you all at the Port of Brownsville notice any changes or impact in terms of commerce between Mexico and the U.S. during AMLO’s first year?

Campirano: Not from a commerce perspective. We continue to be a provider of commodities and steel into Mexico. I think market issues probably affected that more than the relationship with Mexico.

One thing we have seen that is different is that, we were shipping a lot more commodities into Mexico via pipeline. Given the situation in Mexico, a lot of that has switched to shipping refined products into Mexico by truck, impacting the volume and velocity of movement.

On the one hand, we still see a significant demand for product, though the method in which we deliver it has changed. A lot of it was going out by pipeline, now a lot of that has changed and much more of it is going out by truck. There is also the ability to move additional volumes by rail.

If anything, maybe there’s been a change in logistics, but there really hasn’t been a change in the commercial viability or the commercial demand for those commodities.

NGI: Is the product being shipped by truck primarily gasoline?

Campirano: Primarily premium gasoline and ULS diesel. Those are the two highest of the commodities shipped, though significant volumes of jet fuel is also shipped from here.

Interlube Corporation is also located at the port. We describe them often as the Mexican Quaker State, so a lot of lubricants that are sent into Mexico come through here via Interlube. They continue to grow at the Port of Brownsville.

So, for us, the demand for these commodities hasn’t waned and continues to grow, though the method of which we transport has changed.

NGI: Do you think that was a result of, or related to, AMLO’s efforts to reduce fuel theft last year in Mexico, which called for more transport of fuel via truck?

Campirano: That very well might have been the case. It just seems that the methodology in which we were moving the commodity into Mexico changed and now we see a greater shift to transport over the road versus pipeline.

NGI: There have been a lot of pipeline delays in Mexico, which was a big issue last year for the administration. From the Texas side, are there any infrastructure bottlenecks or challenges that have impacted transportation into Mexico?

Campirano: I don’t know that we’ve noticed any bottlenecks. Here at the Port of Brownsville, we continue to move things across the border without delays. Most of it is imported into Mexico, though we do receive some export material. We do receive some heavy fuel oil that we get from Mexico by rail that ends up going to Deer Park for further refinement there. The vast majority of the commodity is moving south.

I think bottlenecks that exist might occur at the border crossings at times, though for the most part the demand continues to move well in both directions. And, as I mentioned, we’re still seeing a lot of interest from others that are looking to the port for new projects. All of our terminals are expanding capacity and are building more and more truck loading and truck rack capability, and rail transloading into their operations, because there continues to be much demand in Mexico.

NGI: What about natural gas? Is there increased interest from U.S. natural gas companies to work with the Port of Brownsville to send natural gas into Mexico?

Campirano: I can tell you companies have come to us, looking at the port as a prospective destination for natural gas, that’s origin may be domestic, and then looking at how to ship it out from the port. As for pipelines, there have been some discussions, but there aren’t any pipeline projects that we are specifically working on at the moment.

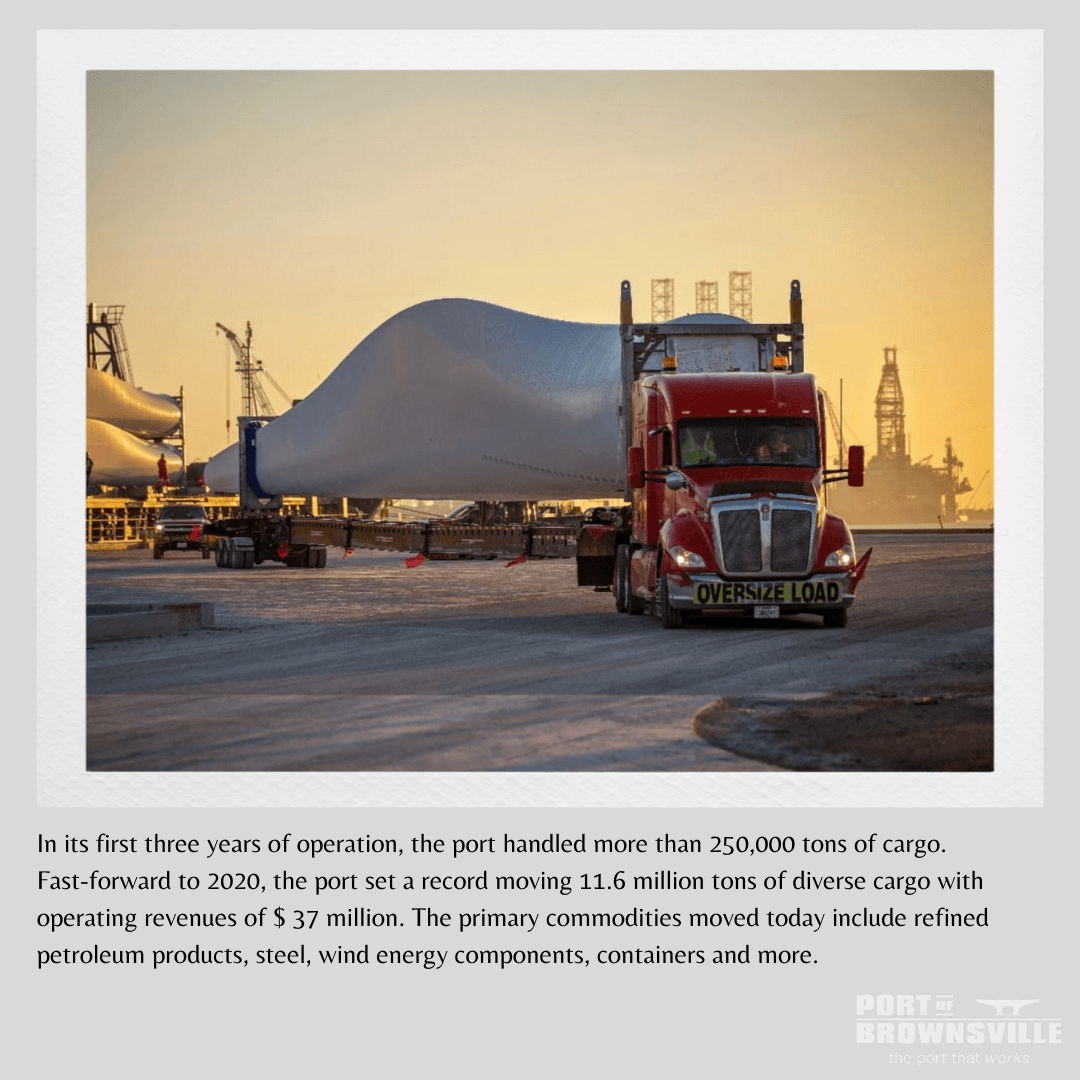

As you know in Texas, the fastest way to get out crude or gas is getting it to the ports, getting it to the coast. When you look at what is happening at Corpus Christi with the amount of crude that is coming out of the Permian basin and when you look at what is happening with the burning off of natural gas, these LNGs are going to play a big role in how that market and resource evolves.

So, you’re going to see that west Texas commodity make its way here. Will it be through natural gas pipelines or additional projects? Yeah, that’s conceivable. But right now, other than what we have on the books and the continued work with Río Grande LNG, everything else beyond that is really just speculation.

The port is going to play a greater role in moving LNG out of Texas. We’re not going to replace a Corpus Christi or a Houston, but we will certainly provide another exit point to be able to move that commodity for export. We’re positioned well for that and are seeing a lot more interest in that.

Ports are going to play a huge role in moving natural gas out of Texas and certainly the eyes are on Brownsville and how our port can assist in getting those products out of the U.S. and into foreign markets.

NGI: It does seem that there is a lot of movement and projects in the works to get fuel and natural gas out of west Texas by “sending it to the coast” as you mentioned.

Campirano: The Permian basin will play a role in supplying natural gas to Río Grande LNG and others. You are going to see more and more of that occurring. That is the most efficient and effective way to get the natural gas volume that is necessary to operate those facilities and meet market demand.

NGI: Looking ahead, what do you forecast at the Port of Brownsville in terms of the evolving relationship between the U.S. and Mexico and what lies ahead?

Campirano: We’ve always been very bullish on Mexico. Given where we are and what we do, we’ve been active participants in the historic trade relationship that exists between the two nations. Without Mexico, Texas wouldn’t be one of the world’s largest economies. We believe the relationship between the two countries will continue to grow as we move forward.