At Brownsville, a gateway for steel into Mexico, bilateral trade shows no signs of cooling

BY JUDE WEBBER / Financial Times

Article published Tuesday, July 24, 2018

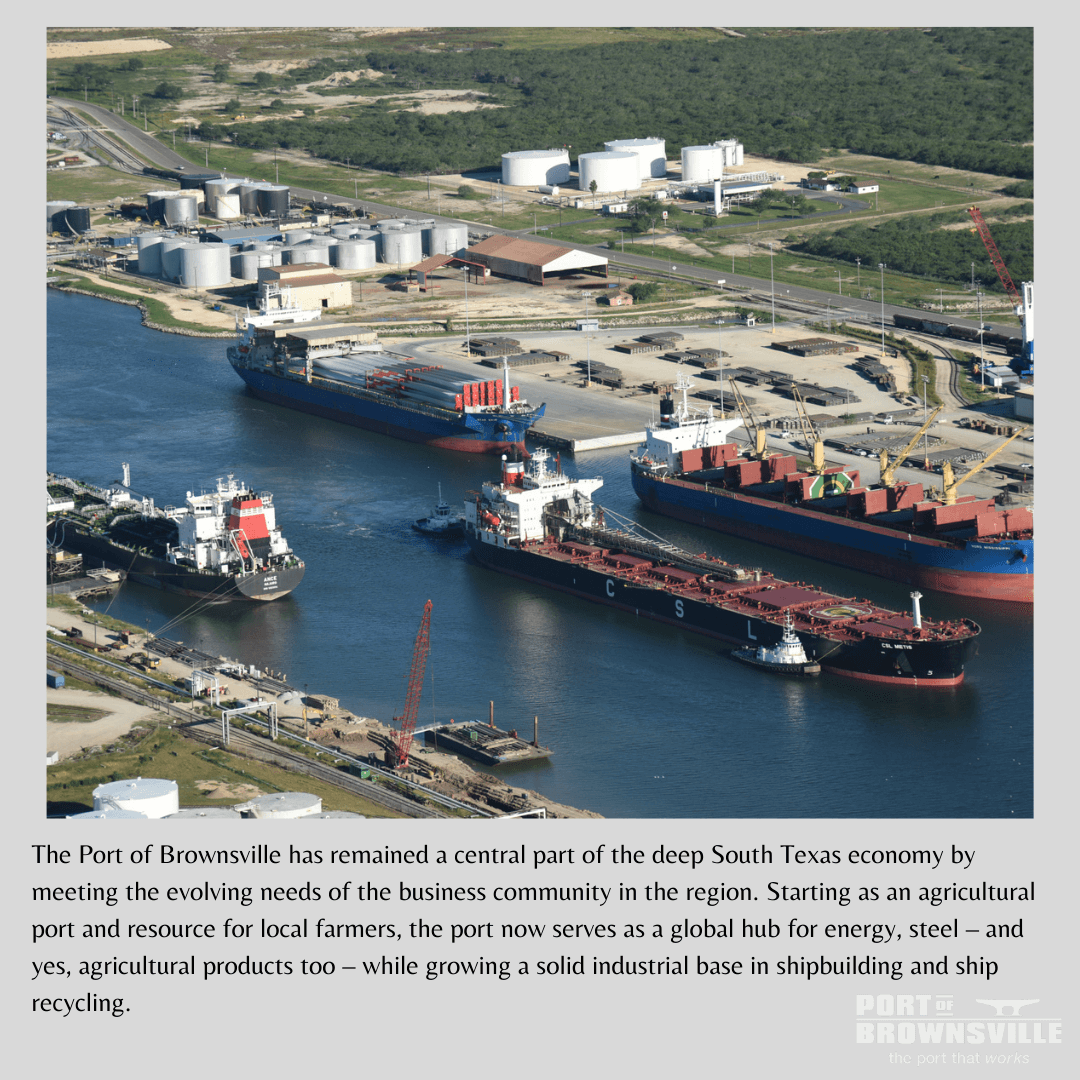

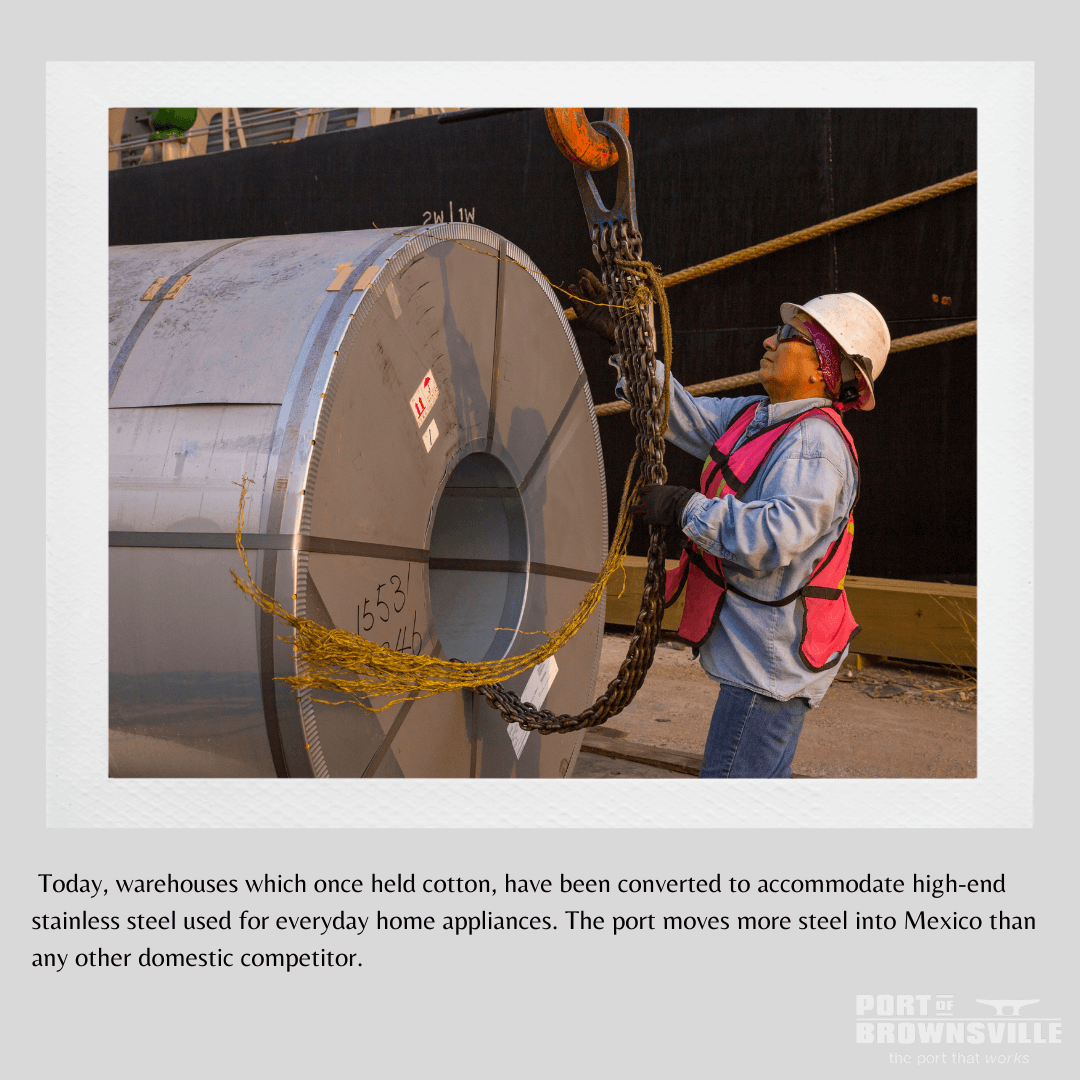

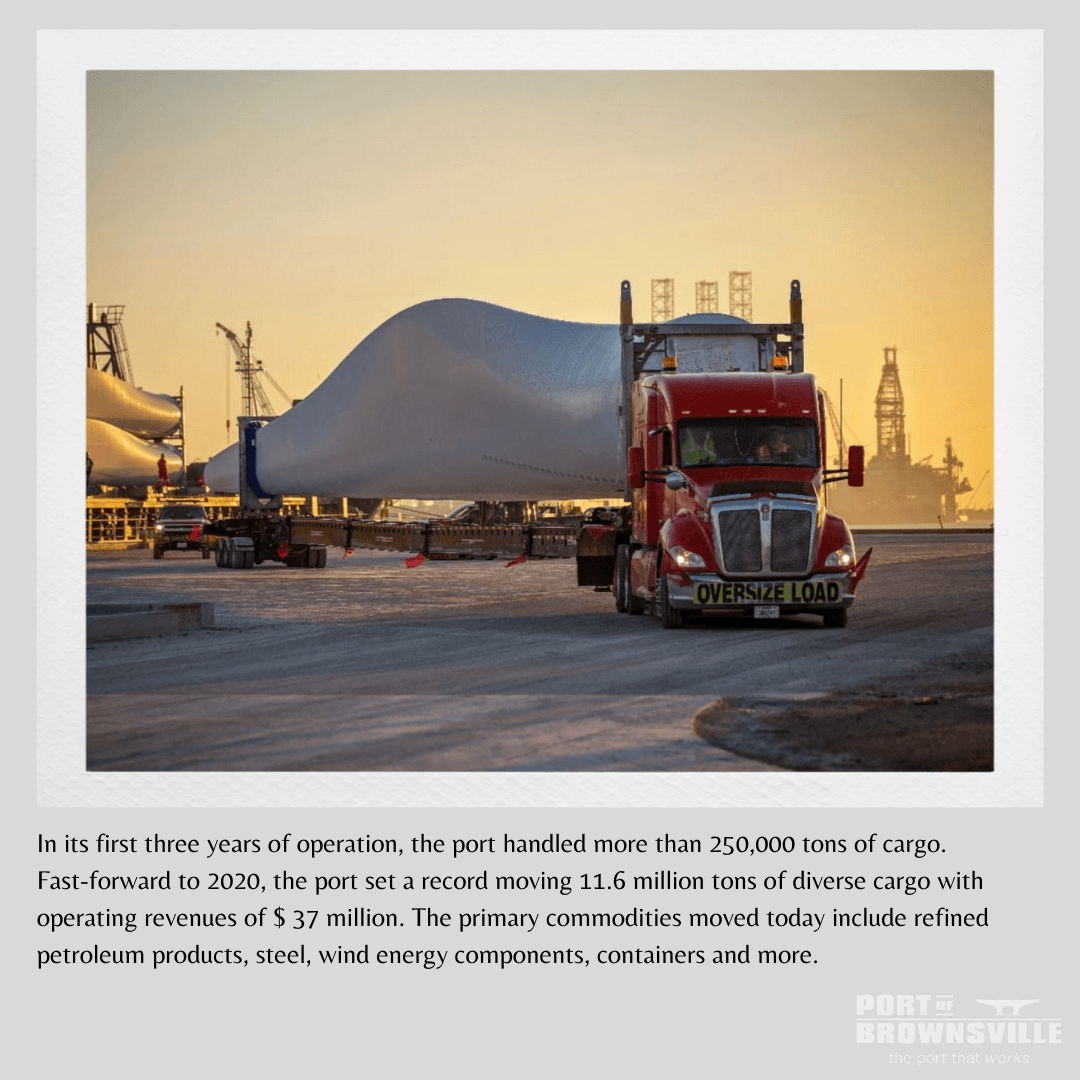

A huge crane unloads giant steel slabs off a ship from Russia, destined for factories in Mexico. Queues of trucks, some of the 800 a day heading across the border, fill up with oil products. Steel coils, animal feed, sugar and colossal wind turbines lie in warehouses or lots awaiting their journey south.

This is the Port of Brownsville in Texas, the biggest gateway for steel into Mexico, a big handler of US oil products heading over the border and the front line in Washington’s escalating trade war with its neighbour and Nafta partner. The US ratcheted up tensions this month by filing complaints against Mexico and other countries at the World Trade Organization.

Yet so far US and Mexican tariffs have failed to dent cross-border business here and booming bilateral trade shows no sign of cooling. US-Mexican trade rose 10 per cent in the first five months of this year to $249bn, versus the same period in 2017 when Donald Trump’s presidency began. Meanwhile the US trade deficit rose 2 per cent to $30.6bn over the same period, according to US figures.

“We have not seen any impact yet. We’re waiting to see but our customers don’t appear to be too concerned,” said Eduardo Campirano, the port’s chief executive. “Our primary steel mover is just as aggressive as last year and is talking about increasing throughput.”

With 95 per cent of its cargoes heading to Mexico, Brownsville has boosted trade volumes by 50 per cent and almost doubled revenues since 2008 and, at $5.3bn, the foreign-trade zone that it administers is the second biggest in the US by export and import value. Whatever happens with tariffs, “trade won’t dry up,” said Shannon O’Neil at the Council on Foreign Relations.

On June 1, Mr Trump used national security arguments to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum, including from Mexico, as the countries struggled to make headway after nearly a year of talks to upgrade the North American Free Trade Agreement. Mexican retaliation was swift, in the form of tit-for-tat duties on steel and an array of US exports, from cheese and pork to apples and bourbon that the US this month challenged at the WTO.

“It’s hard to imagine a port being so sanguine about the impact of tariffs,” said Antonio Garza, a former US ambassador to Mexico and Brownsville native. “Ultimately they are corrosive and trade restrictive, not expansive.”

“Brownsville will be able to weather the tariff storm,” said Chris Wilson at the Wilson Center. “With the US economy growing at a healthy rate, the demand for steel will remain high, meaning import volumes will stay strong. Of course prices will go up, but they will be pushed as far down the supply chain as possible.”

Whereas a diversified port can adapt to changing markets, the deeply entwined cross-border auto and manufacturing industries show how much is at stake for Mexico. “Maybe Brownsville doesn’t care if it’s oil or steel but it could have a big impact on workers in Mexico,” Ms O’Neil said.

Part of the reason Brownsville has proved resilient is its location. “It is a very good gateway into Mexico . . . You won’t find another port to replace it that easily,” said Bill Ralph, a marine economist at consultancy RK Johns & Associates. “Brownsville has the logistics connections that most ports can’t offer.”

At the same time, with Brownsville mostly handling steel in transit to Mexico, it is unlikely to be hurt by steel tariffs on US imports in the same way as other ports, he said. If Mr Trump invokes national security rules against car imports, “there isn’t any US port or border crossing that wouldn’t feel some effect”, Mr Ralph said.

For now, it is business as usual at this deepwater seaport. The Russian steel is bound for Monterrey, Mexico’s industrial capital just 200 miles away. “We haven’t seen any indication this [tariff war] is going to hurt us,” said Donna Eymard, deputy port director.

Nor have the tariffs dented planned investments. A $1.6bn Big River Steel mill on port land is at the due diligence stage. “If their market is Mexico, they can benefit from all the logistical advantages, save a lot of money and have higher margins even if punitive tariffs apply,” said Steve Tyndal, senior director for marketing and business development at the port.

In addition, three companies — Annova LNG, Rio Grande LNG and Texas LNG — are in the final stage of obtaining permits to build a trio of gas liquefaction plants representing nearly $39bn in investment that could make Brownsville the top US LNG export hub, Mr Tyndal said.

Sprawling across 40,000 acres that are also home to eagles and giant tarantulas, the port has adapted to other crises. “When there was the devaluation of the peso [in 1994], we thought it was going to kill us, but it turned out to be one of the best years we had,” said Antonio Rodríguez, director of cargo services, who has been at the port for 26 years.

Steel, renewable energy and other cargoes passing through Brownsville could increase under Mexican president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who takes office on December 1. He wants to boost the domestic oil industry to make Mexico less reliant on US fuel and to invest in infrastructure and development in Mexico’s poor south.

“We are optimistic there are always opportunities for us,” said Mr Campirano. “We could be an exporter of Mexican refined products down the road.” Or as Ms Eymard puts it: “It’s like when you drive your car to the grocery store. There are different routes but you take the one you know. People don’t change.”

https://www.ft.com/content/13cba8b0-89ea-11e8-bf9e-8771d5404543

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018. All rights reserved.